Every decade or so something comes along that changes the way people approach playing the guitar, and, because of it's central focus in most popular music, it changes the way many genres of music are played. The tremolo bridge is one of those changes.

A tremolo bridge holds the strings at the tail end of the guitar, usually has a tremolo arm and allows the guitar player to apply a varying degree of vibrato to a note or chord by using the arm to apply or relieve the tension on the strings. Interestingly, what we call a "tremolo" is actually a "vibrato." Vibrato is a change in pitch where a tremolo is a change in volume. But, way back in the day, Leo Fender patented a unit for the Stratocaster called the synchronized tremolo and we've called it that ever since.

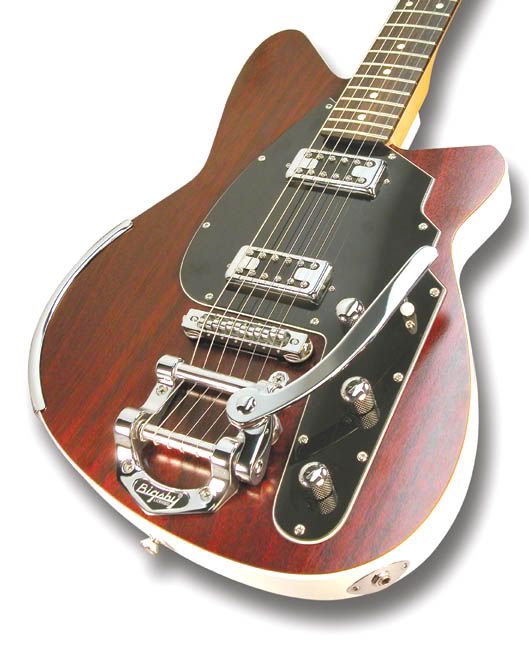

The first commercially successful tremolo/vibrato unit was the Bigsby vibrato tailpiece. It incorporates a spring loaded tremolo arm, or whammy bar that controls the tension of a bar that crosses all six strings. The bar raises or lowers to release or increase tension on the strings causing the pitch to lower or rise.

The first commercially successful tremolo/vibrato unit was the Bigsby vibrato tailpiece. It incorporates a spring loaded tremolo arm, or whammy bar that controls the tension of a bar that crosses all six strings. The bar raises or lowers to release or increase tension on the strings causing the pitch to lower or rise.There were some downsides to the Bigsby unit. First, the change is pitch is relatively moderate. When first introduced, rockabilly players used them to add vibrato to their melodies. But as people sought more extreme pitch changes, the Bigsby couldn't really deliver. Second, raising notes by pushing down on the arm was no problem, but lowering notes by pulling up became an issue. When pulling up too high, the spring could fall out.

Despite these problems, the Bigsby is a popular unit and is still used on many classic hollow-body rockabilly guitars and special model Les Pauls and the like.

However, Due to these problems, Leo Fender created the synchronized tremolo which popularized the term tremolo (Leo was an engineer, not a musician).

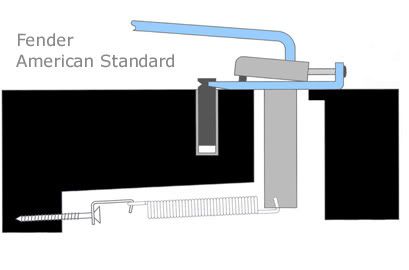

However, Due to these problems, Leo Fender created the synchronized tremolo which popularized the term tremolo (Leo was an engineer, not a musician).Rather than simply screwing to the top of the guitar, the Fender tremolo actually passes through the body, as shown in the diagram. It allows greater control over pitch changes and you don't have to worry about losing any springs. You can see that the spring tension is maintained at the bottom of the route (it also passes string vibrations to the body of the guitar this way -- leading many people to believe that these springs were part of the classic Fender mojo). The unit is held in place by and pivots on, two screws. The bridge has special partial circles that partially encircle an indent under the screw heads. This treolo unit also changed the way you changed the pitch. Now, string tension is directly effected by the whammy bar as the entire bridge is moved. Pushing the bar down, toward the body, causes slack in the strings as the bridge is moved forward. Pulling the bar up, the bridge moves back, increasing tension and raising the pitch.

Just about any guitarist you can think of has, at one time or another played a guitar with this style tremolo bridge.

Just about any guitarist you can think of has, at one time or another played a guitar with this style tremolo bridge.Not only has this tremolo fundamentally changed music. It has spawned many licensed copies. Pictured here is one of the best -- a Wilkinson tremolo unit. It smooths some edges and is a bit more playable than a factory Fender unit. This unit has such popularity that Fender has begun installing Wilkinson units in their high-end model guitars.

The issue with Fender-style tremolos is tuning. If you've ever heard any Jimi Hendrix songs live, you know he beat the hell out of his whammy bar. You also know that half way though songs he suffered tuning issues. Feedback and the very sloppy distortion of the era helped hide this. Todays compressed, chorused, tight digital recording environments would never allow for this. Even in the late '70s, as recording and live sound got cleaner and mistakes and sound variances became more apparent, guitarists sought greater tuning stability.

Enter the Floyd Rose double-locking tremolo. This is probably the last truly significant change in tremolo/vibrato technology. While there have been improvements and tweeks, the double locking system revamped, again, the way people approached guitar playing.

Enter the Floyd Rose double-locking tremolo. This is probably the last truly significant change in tremolo/vibrato technology. While there have been improvements and tweeks, the double locking system revamped, again, the way people approached guitar playing.Introduced in 1979, the system is similar to the Fender tremolo in that it passes through a route in the guitar body. Tension is provided by the same springs in the same place as the Fender system. The difference is that the Floyd Rose bridge locks the strings in place with a little block. You cut the balls off the end of the strings and the strings lock in place. THEN, you tune the guitar and the strings are locked at the top of the guitar with a special locking nut. This creates extreme tuning stability and spawned the divebombing and extreme pitch modulation style of play among the heavy metal guitarists of the '80s. Eddie Van Halen probably did more to create the style, but Steve Vai is the certified master of tremolo play.

Today's tweeks have involved a variaty of ways to produce this double locking system. In the late '80s, engineer Ned Steinberger introduced a series of "headless" guitars where the ball end of the strings are at the former headstock end and the strings are tuned at the bridge. This is one of the most stable tuning systems and allows some of the most extreme style of play. However, the headless neck was a bit extreme to most guitarists and it fills a very niche market.

Recently, guitar manufacturer Ibanez introduced the Edge Pro style tremolo. It's very similar to the Floyd Rose style trem, but you don't have to cut the end of the string off and it eliminates many of the sharp edges that the Floyd Rose has.

Recently, guitar manufacturer Ibanez introduced the Edge Pro style tremolo. It's very similar to the Floyd Rose style trem, but you don't have to cut the end of the string off and it eliminates many of the sharp edges that the Floyd Rose has. Another solution people use is to continue to use a Fender-style bridge but use locking tuners creating tuning stability. It's a popular solution for people who like the ability to change their strings quickly like a Fender but like the tuning stability of a Floyd Rose.

Me? I prefer no tremolo. Give me good ole tune-o-matics. But it's always good to know your instrument.

No comments:

Post a Comment